|

It

is a peculiar irony that the most famous of all

the Mohawks—arguably the most well-known nation of the

Rotinonhsón:ni (Iroquois) Confederacy—is a 17th century woman

who, by her vow of celibacy, isn’t an ancestor to any of us.

A New Biography “Repatriates”

Káteri Tekahkwí:tha, the Lily of the Mohawks A new book by Blessed Káteri Tekahkwí:tha*—the Lily of the Mohawks—tells her story from the perspective of her own people, just as the cause for her canonization as the first Native American saint reached an important milestone. Káteri was declared venerable by Pope Paul Pius XII in 1943, and declared blessed by Pope John Paul II in 1980. It was not expected that John Paul II would be the one to canonize Káteri, since he presided over her beatification. With his death and the appointment of his successor, there was a renewal of hope that Káteri might soon be recognized as a saint. Mohawks of the Lily

Among her people, the prospect of sainthood for Káteri Tekahkwí:tha draws a mixed reaction. Many of them are Roman Catholics, especially among the three Mohawk communities in valley of the St. Lawrence River, but there are many who reject any form of Christianity in favor of the old ways of the Longhouse. In a sense, it is a reversal of what happened during Káteri’s life, when Christianity first made its way into the old Mohawk Valley. For those who were brought up in the Longhouse, Káteri’s canonization is of as little interest to them as the goings on at Mass every Sunday. But for those who were raised Roman Catholic and later “converted” to traditionalism, Káteri is like a family member who remains staunchly Christian while they follow a different path. It is a peculiar irony that the most famous of all the Mohawks—arguably the most well-known nation of the Rotinonhsón:ni (Iroquois) Confederacy—is a 17th century woman who, by her vow of celibacy, isn’t an ancestor to any of us. Among her people, knowledge of the details of her life remain somewhat superficial. It’s as if she has always been a porcelain icon: her memory has been so thoroughly appropriated that even her own people speak of her in terms taken verbatim from the writings of others. For a nation that has labored for the repatriation of human remains, wampum belts, false face masks, and other significant items held by museums and universities, we seem to have neglected something just as important—the memory of one of our own. The study of her life offers us a window into the tumultuous 17th century, a time that brought unprecedented change to the Mohawk. Káteri Tekahkwí:tha lived through two of the most pivotal events in our history: the burning of our villages by the French army in 1666, and the relocation of many of our people to the St. Lawrence River in the decades that followed. During her life, the colony of New Netherland changed hands from the Dutch to the English and became New York. The archaeological evidence from the villages where she lived indicate that the Mohawks were undergoing a major transition in their material culture, moving from clay pottery and bows and arrows to brass kettles, tools, and firearms. It was also a time of suffering, as the scourge of smallpox swept through our villages, killing hundreds—including the immediate family of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha. For those interested in learning about this history, finding reliable material hasn’t always been easy. It has long been the tendency of scholars to focus on traditional Iroquois culture, leaving the story of the Christian converts to the more devotional writers. This resulted in two divergent streams of literature that rarely intersected. In recent decades, anthropologists such as David Blanchard, Daniel K. Richter, John Steckley, K. I. Koppedrayer, Nancy Shoemaker, William B. Hart, Christopher Vecsey, and Allan Greer began to pay closer attention to the story of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha and Jesuit missionary work among the Iroquois. Mohawk scholarship, on the other hand, has largely focused on the traditional ways of the Longhouse and the history of the Iroquois Confederacy. A New Biography

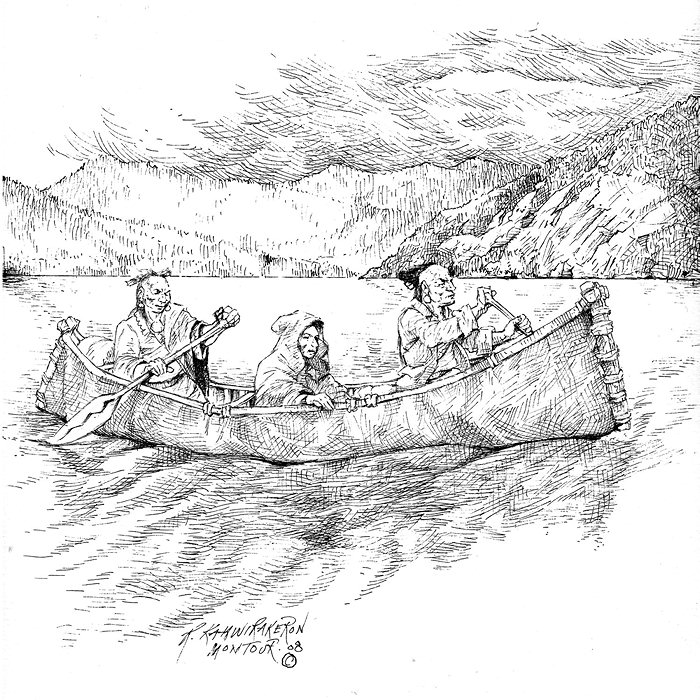

This will all change with the publication of A Lily Among Thorns: The Mohawk Repatriation of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha by Darren Bonaparte, the Mohawk author of Creation & Confederation: The Living History of the Iroquois and the creator of The Wampum Chronicles: Mohawk Territory on the Internet. Bonaparte’s new book focuses on the era of European contact and the advent of Jesuit missionaries among the Mohawk in the 17th century. A Lily Among Thorns is a biography of Káteri Tekahkwí:tha, drawing from the writings of the priests who knew her personally, as well as documents from French, Dutch, and English colonists. There is also considerable information about what archaeologists have found about the villages where she lived in the Mohawk Valley. According to Bonaparte, “I take a much more critical look at the Jesuit writings than any biographer has ever done before and try to flesh out the real Mohawk woman behind the romanticized icon.” Of particular interest to Bonaparte was the way the Jesuits painted her non-Christian family and neighbors in the worst possible light to emphasize her virtues. “The ‘saint among savages’ theme has always been a major component of the Káteri biographies, and it is one of the reasons why most Mohawks don’t bother reading them,” he says. “The non-Christian Mohawks have been the villains of her story for far too long. I felt it was time to give them their day in court.” Bonaparte suggests that there was more than just religious devotion that motivated a large segment of the Mohawk population to leave their homeland for the valley of the St. Lawrence River. “Most Káteri books leave out the fact that the French army came down from Canada and burned our villages to the ground in 1666, which prompted the Mohawks to reconsider keeping New France as an enemy,” he says. “It was in their best interests to allow a Mohawk satellite village to be established across the river from Montréal, where we could keep an eye on troop movements and have another market for the fur trade.” Bonaparte presents considerable information about the burning of the Mohawk villages, which occurred when Káteri Tekahkwí:tha was only about ten years old. “Seeing such a massive army marching toward their villages with drums thundering away to announce their approach, the Mohawks abandoned their villages and fled. The French wrote that they found enough food stored in those villages to feed all of Canada for two years.” The following year, Jesuit priests were allowed into the rebuilt Mohawk villages to establish missions. Eventually one of these missionaries baptized the adopted daughter of a Mohawk chief. This young woman eventually joined the Mohawks who departed for Canada and the new village of Kahnawà:ke in what is now Ville Sainte-Catherine, Quebec, just east of the current Kahnawà:ke reserve. Her name is known throughout the world as Káteri Tekahkwí:tha. “Her arrival in Kahnawà:ke marks the beginning of what I feel is the most controversial aspect of her story,” Bonaparte says. “The converts began to imitate the severe penances that the Jesuits practiced. They whipped themselves, plunged themselves in ice-cold water, and even burned themselves, all in the belief that by sharing in the suffering of Jesus Christ, they would prove themselves worthy of salvation. The Jesuits did not adequately discourage these extreme acts, but instead marveled at them.” Káteri Tekahkwí:tha, who had always been sickly, died after laying on a bed of thorns for three nights. Instead of admitting any culpability in the death of one of their charges, the Jesuits began to promote her as a saint, especially when she began to appear to people in visions and was responsible for miraculous cures throughout New France. “I have no doubt that Káteri Tekahkwí:tha had a powerful spirit,” Bonaparte says. “She continues to have a presence in our lives today. My criticism of the Jesuits does not diminish her power in any way. They’ve always had the last word on her story, since they were the ones who wrote it for so long, but we owe it to Káteri and her companions to be a bit more critical of what they wrote.” “In the end, people will come away from this knowing Káteri Tekahkwí:tha better than they ever have before,” Bonaparte says. “Regardless of your feelings about the Church or the Longhouse, you will see a flesh-and-blood Mohawk woman emerge from the mists of time, and she will proceed to make herself right at home.” * Káteri Tekahkwí:tha is the standardized Mohawk form of Kateri Tekakwitha. According to author Darren Bonaparte: “I have always heard this pronounced in as Gah-deh-LEE Deh-gah-GWEE-tah. Kateri is similar to the way the French pronounced Katherine. Kateri does not rhyme with battery.” |

To Purchase

If

you’ve

arrived at this page from a search engine,