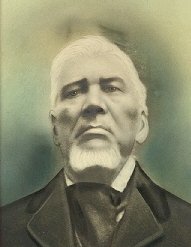

A Gift to the Seventh Generation The Legacy of Loran "Kanonsase" Pyke by Darren Bonaparte The documents, which had been kept in an old metal tool box at the old Pyke homestead, were yellow with age but in remarkably good condition. Almost every word was in Mohawk. The documents consisted of old sheets of paper, envelopes, recycled grocery bags, stationery, and an old ledger book with a worn cover and missing pages. Feeling like Indian Jones discovering the Holy Grail, I gently flipped through page after page of the ledger book, wondering what kind of historical information it contained. The dates of these documents ranged from the 1870's to the 1920's, an era in which Akwesasne endured many changes, from forced elections and the introduction of schools, to the loss of vast tracts of Mohawk land during suspicious land deals. Gus relayed what his father, the late Joseph "Harry" Pyke, had told him about the man who wrote the documents: it was Loran "Kanonsase" Pyke, Harry's great great grandfather, who had been a clerk and a chief in the village of Kanatakon in the late 1800's and the early 1900's. It occured to me that Kanonsase would have been an eyewitness to many of the crucial events of his time. With the permission of the Pyke family, I was allowed to make copies of the documents and to have them microfiched. The originals were then placed in protective plastic sheaths and an archival storage box and returned to the family. With the photocopies in hand, I began to peruse them with the objective of finding the first ones to begin translating. Several early documents stood out: one was a copy of an earlier document dating back to the founding of the village of Kanatakon, which contained the names, clans, and the some of the descendents of the first Mohawks to come from Kahnawake in 1759; another was a list of Mohawk participants in the War of 1812 who fought the Americans near Niagara Falls. These were heavy documents, to be sure, but the document I chose for the first translation was one that bore the magical date of February 16, 1888. February 16, 1888 was a "magical date" because of something which was alleged to have happened at Akwesasne on that day. It was a day shrouded in mystery and darkness, as if a cloud hovered over the village of Kanatakon through which the sunlight of modern knowledge was unable to break through. From what I had learned during my day-to-day work at the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne's Aboriginal Rights and Research Office, I knew that this was the date of the alleged "surrender" of the lands at Dundee. On February 16, 1888, the "Kora" came to Akwesasne. "Kora" was the Mohawk name for the Superintendent-general of Indian Affairs, an honorary title handed down from the time when the Dutch controlled the colony that was to eventually become the state of New York. What brought the Kora to Akwesasne was a meeting with the Mohawks concerning a matter of great importance, the Dundee land situation. The lands of Dundee, or Tsikaristisere, had been leased out by the Mohawks to French and English settlers for years. When the leases began to run out, the settlers put pressure on the government to effect a new arrangement with the Mohawks. A public inquiry was held by the name of the Burbidge Commission. This commission heard testimony from more than 150 non-native settlers and only 5 or 6 Mohawks. The Mohawks were not told of the contents of the final report, which recommended that the Department of Indian Affairs secure the surrender of the Dundee lands to Canada. Only three days after the Burbidge Commission was released, the Department of Indian Affairs began the process of securing this "surrender" by inviting the Mohawks to a meeting to discuss the future of the Dundee lands. This meeting was held on February 16, 1888, the coldest day of the year. Aside from the few Mohawks who had farms at Akwesasne, the majority of the people were away from Akwesasne for the winter due to the lack of wood to adequately heat and winterize their homes. Those that were present at this meeting spoke very little or no English and had to rely on interpreters to understand the presentations put forward by the Canadian government officials. Mohawk elders living today and those who have sinced passed on to the Creator's land have always insisted that there was never a surrender of this land, that the Indian Agent and the Department of Indian Affairs pulled a fast one that resulted in our people losing these valuable lands. Up until the Kanonsase document came to light, however, the only documentation about this meeting was the record of the Department of Indian Affairs, which did not include what the Mohawks had decided among themselves during their private deliberations, or their perceptions of what was occurring. Thanks to Kanonsase and his descendents, we now have a transcript of what the Mohawks decided for themselves, and it confirms beyond a doubt what the elders have said all along: "We never surrendered the lands in Dundee." I assembled a group of Mohawk elders from all areas of Akwesasne to begin a formal process of translation. The document was transcribed and then updated into modern Mohawk spelling standards by Dan Thompson of the Kanienkeha Curriculum Centre, who then drafted an initial translation. The elders then met every few weeks to revise the translation until they were satisfied that it gave a good faith interpretation of the events of the day. After about 5 months, they were ready to present their translation to the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne for their formal acceptance. I was present at the meeting in which Grand Chief Mike Mitchell and the Mohawk Council of Akwesasne formally recognized the Pyke family and the Mohawk elders who participated in the translation project. Gus and his daughter, Kiera, representing the seventh generation since Kanonsase himself, accepted a plaque on behalf of the family of Joseph "Harry" Pyke. It was a proud moment for me not only as the historian who was entrusted with the documents, but as a cousin of the Pyke family and a Mohawk of Akwesasne. |